Notes

from my desk.

The curtain

The Martin Parr Foundation has asked me to be a judge for their new bursary. It’s a real privilege to be involved—especially because I get to work with their team again.

That said, judging one artist over another is daunting. It feels odd to be on the other side.

I was thinking back to 2020, when I applied for the same bursary during the Covid lockdown. Full of doubts about the work but with nothing better to do, I applied. Half hopeful but expecting nothing to come of it.

Somehow it got chosen and the most transformative thing was seeing the work alongside the other projects also picked. It changed how I saw myself -as having potential as an artist. It made me raise my game and allowed the work to exist outside my imagination. No small thing.

That was the first of many game-changing moments that followed thanks to the guidance of Martin Parr and the support of the Martin Parr Foundation. I can’t stress how invaluable their support is.

Back then, I was making my first project and figuring out what having a practice even meant. To guide myself, I made a kind of Tony Ray Jones list/manifesto. A mix of advice I’d picked up from books, podcasts, and YouTube.

And now feels like an appropriate time to share it:

1. Have something to say.

2. Make the thing you’d like to see in the world.

3. Don’t worry if you don’t have the skills. Just make the best work you can today. Then do the same again tomorrow. That’s enough.

4. If you’re struggling to articulate your vision in words, don’t worry. Keep struggling -it’ll come. (See 3—because this mindset underpins everything)

5. Don’t compare yourself to other artists. (See 3)

6. Be honest about who you are and where you’re at. (See 3)

7. Say yes to things, especially when they scare you a little.

8. Roll with the punches and keep going.

That’s it.

If you’re unsure about applying, do it anyway. It doesn’t matter if you get it or not (see 3!). Putting yourself in the ring is already a step forward!

And in the spirit of all of the above, I’m sharing some new work, a tryptic from an ongoing project, a tale of three buildings.

Wishing everyone the best of luck. I can’t wait to see what you’re working on.

Seva

I see Bhukan Singh whenever I take my kids Saturday shopping in Leicester city centre. He’s always sitting on the same bench, outside Primark, where the pigeons like to gather. Always immaculately turned out, chatting away in Punjabi to an Englishman who doesn’t understand a word, yet is happy to be in his company.

When he sees me, Bhukan immediately gets up. I can’t see his smile under that thick beard, but his eyes shine. I exchange a hug and a ‘How are you?’ in Punjabi. Then I have to switch to English – which he only half understands, though it’s more than I understand of his Punjabi. Once, I even took my dad to Bhukan’s flat to translate and we could actually have a chat in almost real-time.

I wish my dad were here now. I can tell Bhukan wants to ask me something. He dials a number on his mobile, briefly speaks to someone, and hands me the phone. It’s his daughter. She explains that her father would like to meet Charles and can I introduce him?

‘I don’t know anyone called Charles.’

‘King Charles,’ she replies.

‘Oh.’

I tell her that I’m sorry but I don’t know the king, or how to get hold of him. She apologises for having to ask me and I hand the phone back to Bhukan, but the question lingers. I’m not completely sure of what he said next, but I did catch the word ‘khanna’. From his coat pocket, he pulls out a food bag containing two homemade parathas. I’ve had them before; they’re delicious, but out of politeness I decline, thinking it’s probably his lunch. Then he says something else – the only word I catch is ‘seva’. It’s a Sanskrit term meaning ‘selfless service’ and embodies the spirit of helping others without any expectation of reward. It is a profound practice in many Indian religions, promoting compassion, humility and a sense of community.

I take a paratha and can’t help but eat it right then and there. ‘I should be doing seva for you,’ I tell him, mouth half full. He smiles and shakes his head, concealing any disappointment about the king. This warm, generous, and kind-hearted man embodies the spirit of seva and I think that’s what he sees in the king: that his service to the country is a form of seva to his subjects. It’s a deep respect shared by many British Indians from his generation, and as an artist, it’s something I want to understand more. I’ve known Bhukan ever since I made a picture of him in his home a few years back. When the Southbank Centre commissioned a 20-foot-tall mural of the picture for the outside of the Royal Festival Hall, it made us both very proud. Maybe he’s thinking what I’m now thinking: Royal Festival Hall. Must have some links to the king, right? My mind is whirring. How do I get Bhukan Singh to meet the king? This will be my seva, I decide.

I’ll write to the Palace.

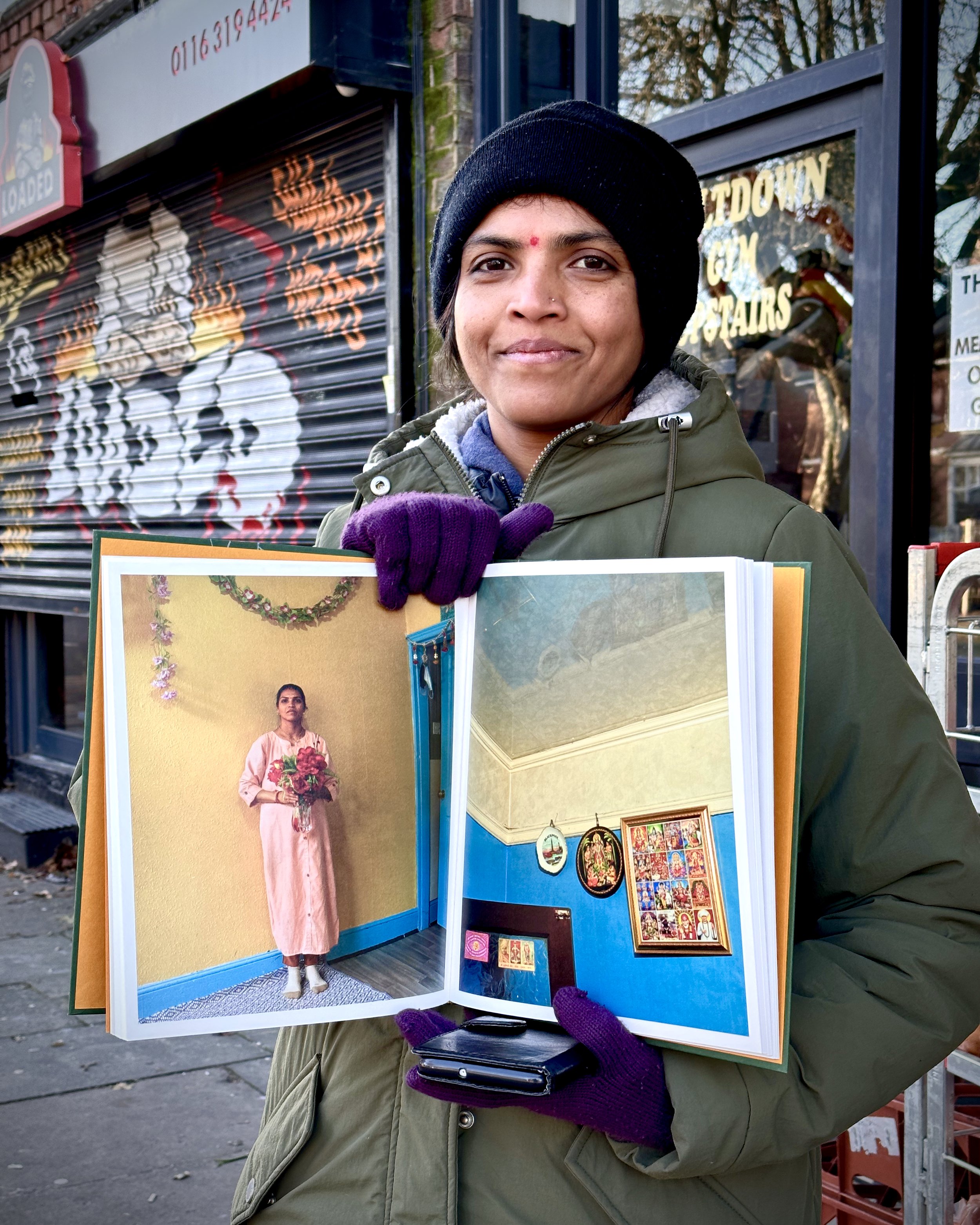

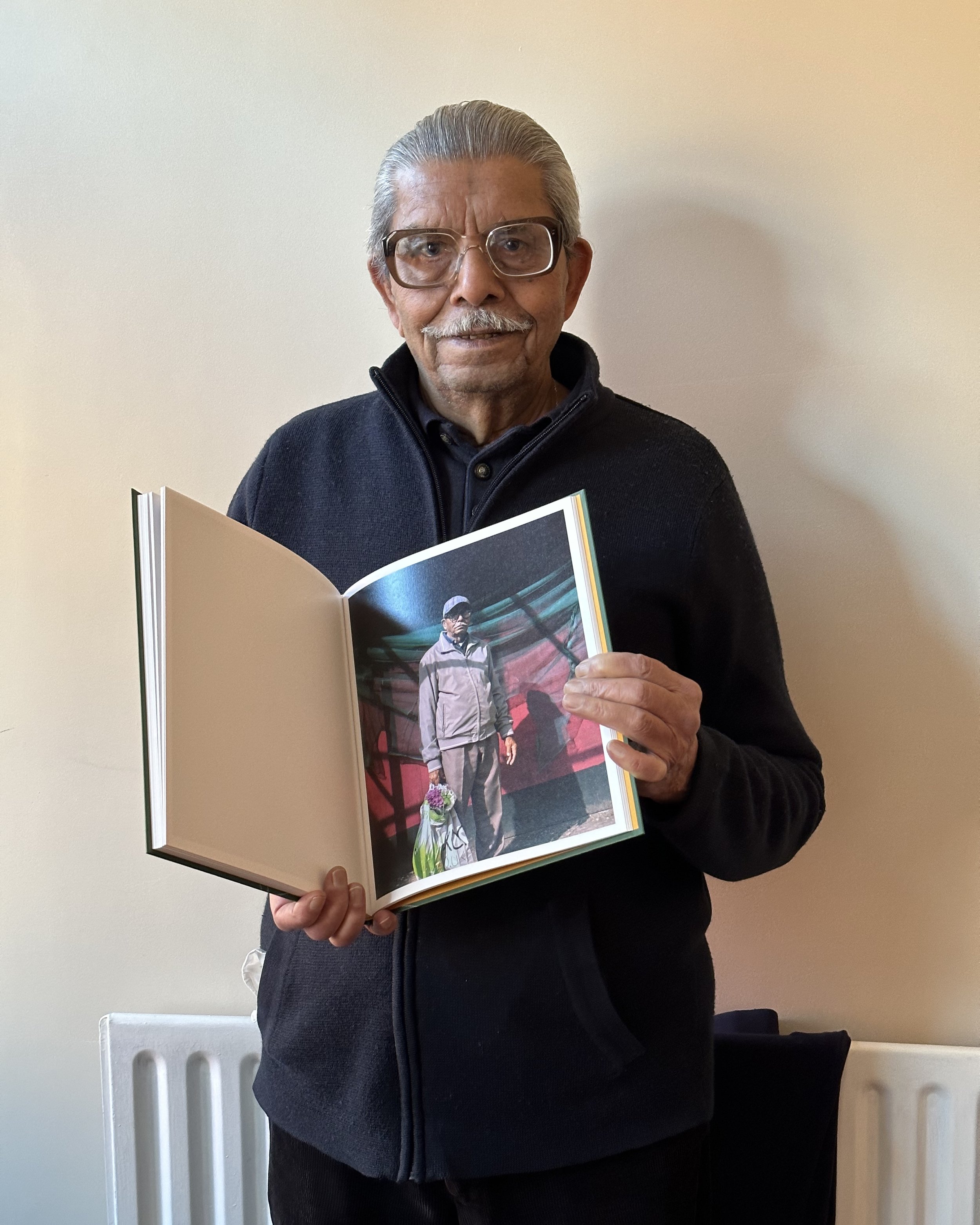

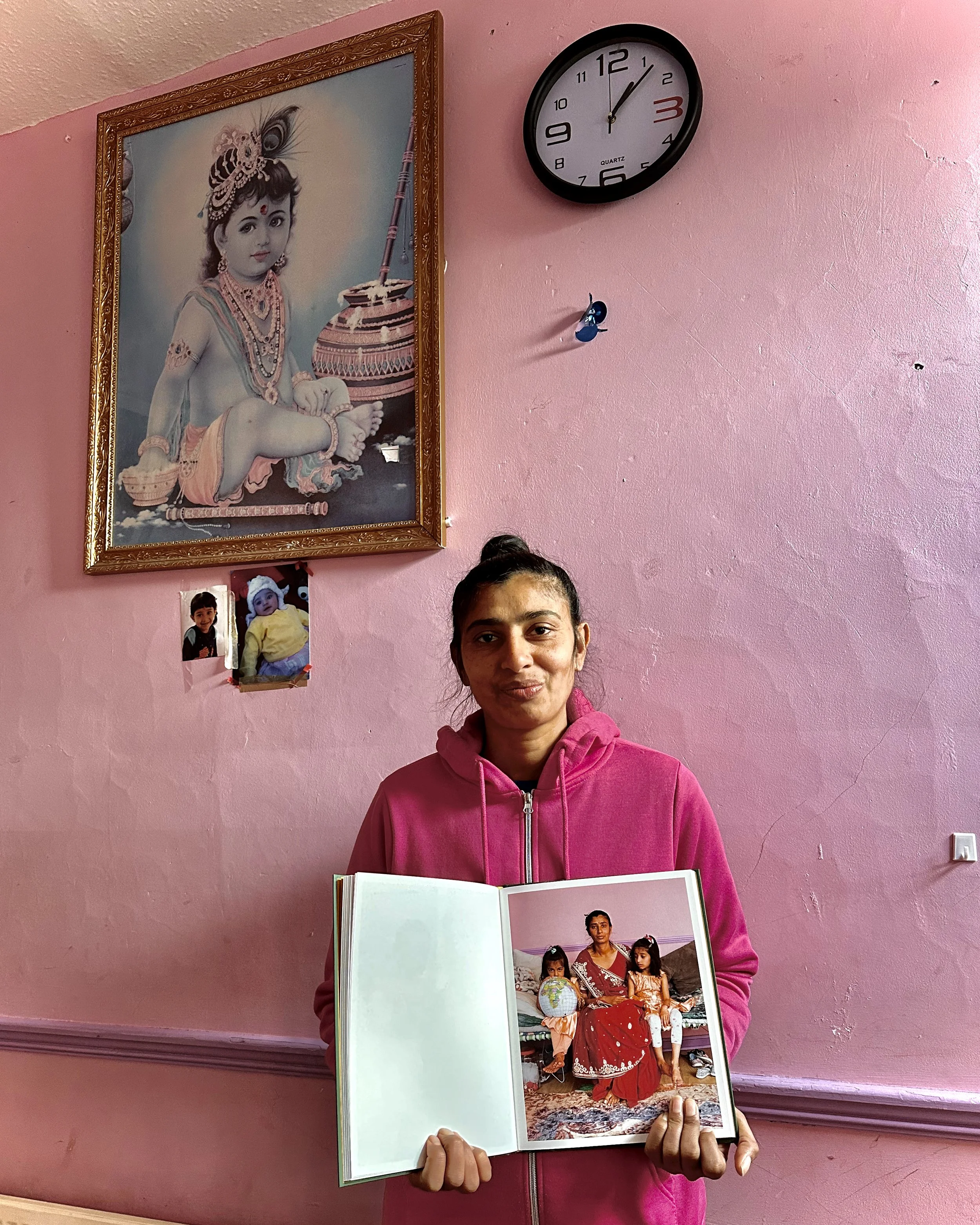

Books in the Community

When I began This Golden Mile, I had only intended to make a photo book or an exhibition. The main reward was that physical object or event at the end of a process of making. The real prize, however, was already being received. --The act of making, the conversations had over numerous cups of masala chai, and friendships formed.

These are only a few pictures of the participants receiving copies of This Golden Mile kindly gifted by so many Go Fund Me supporters in December 2022. I'm very grateful. Thank you.

On Connection

I’ve been invited to several talks with young photographers about my practice this year. I’m always asked about my favourite photobooks, and I love answering that. But there's one book that I recommend to everyone, not just photographers, because I believe it holds a message that resonates with us all. Kae Tempest urges us to move away from consumption, find our creativity and use it to connect with ourselves and those around us. Kae Tempest is one of our generation’s most important voices.

Taking Photos, Giving Prints

A crucial part of making This Golden Mile was giving prints back to everyone I collaborated with to make a picture. Here’s a short video of me doing just that.

Arrivals

1970, England: Paul McCartney leaves The Beatles, Enoch Powell is re-elected as a Tory MP two years after delivering his infamous anti-immigration Rivers of Blood speech, and my mother Sarla (pictured right) celebrated her niece Vishwa’s 16th birthday (pictured left). It's their first summer in the UK, having migrated from East Africa the previous winter.

Their move to the UK was triggered by the Kenyan government’s Africanisation policy in the late 1960s, which stopped issuing trading licenses to non-Africans, forcing Asian business owners to close up and leave the county of their birth.

My Father spent eight months dissolving his business, sending my Mother and Brother ahead of him to the UK to join my Aunt. These women laid the foundations for a new life with few resources or state help. They found accommodation, enrolled their children into schools and found employment while navigating new cultural codes, inclement weather and language barriers.

These were challenging times in a racially-charged England. However, what I love about this image is that they still found time to get dressed up and celebrate a girl turning sixteen without their husbands, fathers or The Beatles.

Barrie Keeffe

Barrie Keeffe was one of my tutors while studying for my Screenwriting MA.

I took this portrait of him on a Sunday afternoon visit to his home in Hampstead. He was a true gentleman, generous with his time and knowledge. Barrie sadly died in 2019.

If you’ve not seen it, I urge you to watch the film adaptation of his play Sus. His play about racist police on the eve of the Thatcher government coming into power in 1979.

“I write plays for those who wouldn’t be seen dead in a theatre.”

-Barrie Keeffe

Calais Jungle

Revisiting a short film I made in an afternoon with the talented Mita Pujara. She wrote this poem about her experience working in the domed theatre space at the centre of the Calais Jungle and then its subsequent destruction. Her words haven't lost any of their poignancy four years on.

Art does have the power to effect change - even if only one heart at a time.

The First Time

Giving Mr Ravat and his wife a copy of the Portrait of Britain 2020 book was an incredible moment. It includes a portrait I took of him. One of many beautiful portraits by nearly two hundred photographers. It was his first time in a book, and mine too. The year of Covid and BLM is also poignantly described in the introductory text by David Olusoga.

“This collection of photographs is a reminder of what we have been missing and of the power of looking into the faces of those with whom we share our nation.”

- David Olusoga

The Lollipop Lady

Laura, Leicester. 2017 ©Kavi Pujara This is Laura. When I was at school in the 80s, Laura was the school lollipop lady (crossing guard). My Mum would take me to school in the mornings, but I would have to run the quarter-of an hour gauntlet home after school by myself. The main danger for a ten-year-old Asian kid were not cars or lorries but National Front skinheads. I knew, come home time, that if I could get to Laura, I’d be safe. I didn't always make it, but on the days I did, she never failed to send the racist skinheads packing.